Transcendental Meditation in the Halls of A.C.T.

By Michael Paller

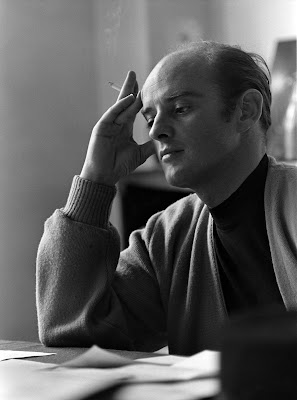

William Ball, founder and first artistic director of A.C.T., had a metaphysical side and was drawn to techniques of meditation for both spiritual and practical reasons. At the all-company meeting that opened the 1982 season and school year, he spoke about the light inside each student. That light was guarded by fear, which had to be overcome before the light—the source of their individual talent—could shine. “Fear is an illusion,” he said, “it is non-productive, it is non-meaningful to us and since it is . . . not a help to us we supersede it. In overcoming a fear we have to trust that nobody is going to hurt the sensitiveness of that light. . . . We create standards of self-discipline that will cause us to respect that sensitivity.”

|

| William Ball. Photo by William Ganslen. |

Part of that self-discipline was Transcendental Meditation (TM), which had been brought to the West by the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in 1959, and popularized by the Beatles in 1968, just after A.C.T. arrived in San Francisco. Everyone at A.C.T., from students to company members to staff, was encouraged to take up TM.

For Ball, TM was not only a way to dissolve fear and other barriers to creativity, it was also a practical technique for actors. Experiencing stressful emotional situations, Ball told the students, is what an actor does. However, unlike a musician, who can put her instrument down and walk away when she’s done, an actor is often left with the stressful emotions she experienced while performing. TM, Ball said, enabled actors to purge those emotions. “Meditation is a technique that will free you of the encumbrance of accumulated stress. That’s why we introduce it as an acting technique.” It had the added benefit, he believed, of adding to one’s quality of life.

To that end, a room on the fifth floor of the company’s headquarters across the street from The Geary was dedicated to meditation. No work was to be done there, Ball told the students; it was strictly for meditation and rest. Everyone at A.C.T. was encouraged to try it. Many found it beneficial and continued to practice it long after leaving the company. Others were less taken with what they regarded as its cultish aspects, including the practice of placing an offering of a flower and a piece of fruit on an altar during the earnest ceremony in which each participant received a mantra from the TM instructor.

For Ball, TM was not only a way to dissolve fear and other barriers to creativity, it was also a practical technique for actors. Experiencing stressful emotional situations, Ball told the students, is what an actor does. However, unlike a musician, who can put her instrument down and walk away when she’s done, an actor is often left with the stressful emotions she experienced while performing. TM, Ball said, enabled actors to purge those emotions. “Meditation is a technique that will free you of the encumbrance of accumulated stress. That’s why we introduce it as an acting technique.” It had the added benefit, he believed, of adding to one’s quality of life.

To that end, a room on the fifth floor of the company’s headquarters across the street from The Geary was dedicated to meditation. No work was to be done there, Ball told the students; it was strictly for meditation and rest. Everyone at A.C.T. was encouraged to try it. Many found it beneficial and continued to practice it long after leaving the company. Others were less taken with what they regarded as its cultish aspects, including the practice of placing an offering of a flower and a piece of fruit on an altar during the earnest ceremony in which each participant received a mantra from the TM instructor.

|

| Judy (Cherene Snow) reads her partner Joan's mantra in A.C.T.'s production of Small Mouth Sounds. |

When an instructor refused an actor’s request to change his mantra, stage manager Jim Haire (who eventually became the company’s producing director) rebelled. He announced to the instructor that he’d taken it on himself to change his mantra to “tiko-tiko”—the title of the Brazilian song that became an American pop hit in the 1940s, sung by Carmen Miranda and the Andrews Sisters. The instructor was appalled. The company was amused. There is no record of Ball’s reaction.

Small Mouth Sounds runs until December 10 at A.C.T.’s Strand Theater, 1127 Market Street. Click here to purchase tickets through our website. Want to learn more about meditation and the production? Order a copy of Words on Plays, A.C.T.'s in-depth performance guide series.