Meet King Charles III Playwright Mike Bartlett: Part Two

By Simon Hodgson

“You can feel it oozing Shakespearean complications," says playwright Mike Bartlett about his play King Charles III, which begins performances at A.C.T.'s Geary Theater on September 14. Over the summer, we caught up with Bartlett to talk about form, pentameter, and King Charles III.

Your play has echoes of several Shakespeare plays. How conscious were you of those resonances, and how deliberately did that influence the language?

It was a very conscious decision to write it in a Shakespearean form. The idea that Charles would become king and would refuse to sign a bill into law came at the same time as the idea of writing a Shakespearean–style play. When I started to write it, I mainly had to practice how to write in this form. What I didn’t do was sit down and study my Shakespeare and go through his plays and deliberately add references. I’ve been brought up on Shakespeare. In Britain, you study his work from the age of 13 all the way through high school, and then I studied it at university, and I’ve seen lots of productions. Any references that come through in the writing instinctively are great, but this wasn’t an academic exercise where I cut and pasted. I was more interested in the dramatic principles of Shakespeare than clever references.

What kind of dramatic principles?

A five–act structure and a central tragic archetypal figure. And a slightly comic subplot written in prose that’s thematically linked to the main plot, which is written in verse—that’s another Shakespearean technique.

How did you write the blank verse?

I knew that I didn’t want to sit there counting the syllables on my fingers, desperately cramming the words into the right places. I went to see Ken Campbell a few years ago—he was an improv genius who’s passed away now—and he said that, in Shakespeare’s day, playwrights wrote speeches in iambic pentameter so that actors could remember them more easily and hold multiple parts in their memories. When the playwrights wrote those plays, the meter was in their bones. The meter wouldn’t be an academic thing. It would just be instinct. So I thought, “I need to practice that instinct. I wrote lines and lines of iambic pentameter, speaking it round the house to myself, trying to get to the point where I might be able to improvise the verse fluidly, hoping that if I could, the writing would be driven by the desires and thoughts of the characters, rather than aesthetics or metric requirements.

How does the verse affect the storytelling?

It’s a way of writing kings and queens that feels appropriate. If you write them speaking as we speak, it sounds reductive, as though you were mocking them. But if they speak in verse, their language has a more formal rhythm and a heightened vocabulary. Also, verse compresses meaning down. You can get more meaning into three words of verse than you can in three lines of prose. The verse is all in service of story and character. It’s never there to be beautiful poetry. I believe that’s also true with Shakespeare. The audience should never sit there going, “Wasn’t the writer of this poetry wonderful?” They should always be thinking, “What does this character want?”

King Charles III opens on September 14 and runs through October 9. Click here to purchase tickets. Read more of our interview with Bartlett, along with other articles about the historical and cultural context of this play, in Words on Plays, arriving soon!

“You can feel it oozing Shakespearean complications," says playwright Mike Bartlett about his play King Charles III, which begins performances at A.C.T.'s Geary Theater on September 14. Over the summer, we caught up with Bartlett to talk about form, pentameter, and King Charles III.

|

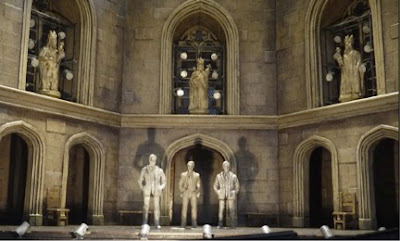

| Set model, by scenic designer Daniel Ostling, for A.C.T.'s 2016 production of King Charles III. Photo by Shannon Stockwell. |

It was a very conscious decision to write it in a Shakespearean form. The idea that Charles would become king and would refuse to sign a bill into law came at the same time as the idea of writing a Shakespearean–style play. When I started to write it, I mainly had to practice how to write in this form. What I didn’t do was sit down and study my Shakespeare and go through his plays and deliberately add references. I’ve been brought up on Shakespeare. In Britain, you study his work from the age of 13 all the way through high school, and then I studied it at university, and I’ve seen lots of productions. Any references that come through in the writing instinctively are great, but this wasn’t an academic exercise where I cut and pasted. I was more interested in the dramatic principles of Shakespeare than clever references.

What kind of dramatic principles?

A five–act structure and a central tragic archetypal figure. And a slightly comic subplot written in prose that’s thematically linked to the main plot, which is written in verse—that’s another Shakespearean technique.

How did you write the blank verse?

I knew that I didn’t want to sit there counting the syllables on my fingers, desperately cramming the words into the right places. I went to see Ken Campbell a few years ago—he was an improv genius who’s passed away now—and he said that, in Shakespeare’s day, playwrights wrote speeches in iambic pentameter so that actors could remember them more easily and hold multiple parts in their memories. When the playwrights wrote those plays, the meter was in their bones. The meter wouldn’t be an academic thing. It would just be instinct. So I thought, “I need to practice that instinct. I wrote lines and lines of iambic pentameter, speaking it round the house to myself, trying to get to the point where I might be able to improvise the verse fluidly, hoping that if I could, the writing would be driven by the desires and thoughts of the characters, rather than aesthetics or metric requirements.

How does the verse affect the storytelling?

It’s a way of writing kings and queens that feels appropriate. If you write them speaking as we speak, it sounds reductive, as though you were mocking them. But if they speak in verse, their language has a more formal rhythm and a heightened vocabulary. Also, verse compresses meaning down. You can get more meaning into three words of verse than you can in three lines of prose. The verse is all in service of story and character. It’s never there to be beautiful poetry. I believe that’s also true with Shakespeare. The audience should never sit there going, “Wasn’t the writer of this poetry wonderful?” They should always be thinking, “What does this character want?”

King Charles III opens on September 14 and runs through October 9. Click here to purchase tickets. Read more of our interview with Bartlett, along with other articles about the historical and cultural context of this play, in Words on Plays, arriving soon!