A Simpsons Lover’s Guide to Mr. Burns, a post-electric play

By Adam Odsess-Rubin

|

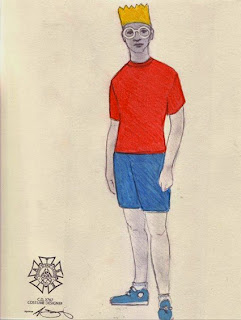

Costume designer Alex Jaeger’s

rendering of Bart Simpson

for A.C.T.’s production of

Mr. Burns

|

The heart of the show is the Simpsons family. Homer, the

father, is an irate buffoon who serves (poorly) as a safety inspector at Mr.

Burns’s nuclear power plant. Marge, the mother, is cautious and thoughtful, and

works hard to keep the family together. Lisa, the older daughter, is the moral

center of the show, a genius and die-hard liberal intellectual. Bart, the son,

is a sassy yellow Dennis the Menace, never found without the slingshot he uses

to terrorize his teachers. Lastly, Maggie is the silent baby, witness to the

family’s antics. Supporting characters, of which there are hundreds, include

Chief Wiggum, an inept donut-eating policeman; Abe Simpson, the forgetful

grandfather who loves to tell war stories from his past; and Mr. Burns, the

evil and greedy owner of a nuclear power plant who would rather block out the

sun than lose money.

Mr. Burns playwright Anne Washburn has pointed to the universal

appeal of The Simpsons as a major reason for its popularity, saying,

“The characters, when you think about them, are durable archetypes—Bart is a

Trickster; Homer the Holy Fool; Marge, I suppose, is a kind of long-suffering

Madonna; and then the inhabitants of Springfield are an almost endlessly rich

supply of human (and non-human) personalities.” But while the goofy family from

the fictional town of Springfield is undoubtably average, they and their fellow

townspeople are also undeniably unique. In large part, the show’s popularity is

due to the fact that it has always encouraged audiences to laugh at, and admit,

their own faults.

|

| The Simpsons creator Matt Groening at the 2012 San Diego Comic-Con International. Photo by Gage Skidmore. |

The Simpsons

has always been visceral and immediate, even in its

earliest renderings as a series of crudely drawn skits for The Tracey

Ullman Show. The show has crafted episodes around immigration

(“Much Apu About Nothing,” 1996), gun rights (“The Cartridge Family,” 1997),

and the environment (“Trash of the Titans,” 1998). Given its penchant for being

current and politically relevant, the show has weathered a fair amount of

controversy. At the 1992 Republican National Convention, President George H. W.

Bush said, “We’re going to keep trying to strengthen the American family, to

make them more like the Waltons and less like the Simpsons.” In 1990, Barbara

Bush said the show was “the dumbest thing” she had ever seen. Of course, The

Simpsons retaliated with a parody—season seven’s “Two Bad Neighbors,” in which the first

family moves in across the street from the Simpsons.

With the ever-increasing popularity of

current-event satirists like Seth MacFarlane (Family Guy), Matt Stone

and Trey Parker (South Park, The Book of Mormon),

Jon Stewart (The Daily Show), and Stephen Colbert (The Colbert Report),

some critics believe it has been difficult for The Simpsons to

keep up in recent years. But it is impossible to deny the show’s influence.

Although critics complain that it can’t measure up to South Park and Family

Guy, these shows wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for the groundwork laid by

Groening almost 30 years ago. MacFarlane acknowledged this debt, saying, “The

Simpsons created an audience for primetime animation that had not been

there for many years. They basically reinvented the wheel.”

It is no coincidence that Washburn chose The

Simpsons as the sole surviving cultural artifact after the apocalypse. The

Simpsons has permeated all aspects of our culture, deconstructing

celebrities, fads, and trends by way of spoof, riff, and satire. Various Simpsons

episodes have tackled film classics from Psycho to A Clockwork Orange

(Hitchcock and Kubrick seem to be favorite targets) and plays from Macbeth

to Rent. The antagonist of “Cape Feare” and regular Simpsons

supporting character Sideshow Bob is a lover of theater. In “Cape Feare,” he

sings songs from the H.M.S. Pinafore and shows off his branded prison

number—24601, the same inmate number as Jean Valjean’s in Les Misérables.

The Simpsons has devoted entire episodes to spoofing Tennessee

Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire (“A Streetcar Named Marge”) and

Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Evita (“The President Wore Pearls”).

Indeed, audiences find pleasure in deciphering the

treasure trove of obscure pop-culture nods sprinkled throughout episodes. The

potency of memory, storytelling, and one of our most iconic pop-culture staples

intersect in Mr. Burns, a post-electric play. As Washburn suggests, even

if a nuclear meltdown or global warming were to destroy civilization as we know

it, it’s likely that The Simpsons would, indeed, endure.

For more about Mr. Burns, be sure to read our latest edition of Words on Plays!

Click here to order online.

For tickets to Mr. Burns visit act-sf.org/burns.