The “Heartprint” of The Orphan of Zhao, How Ink Art Influenced the Production

By Shannon Stockwell

“The centerpiece of this whole play is when Cheng Ying finally has to tell his son who he is. But it’s so painful and frightening that he can’t—so he

paints a scroll. Cheng Bo looks at his life in the scroll and discovers who he

is,” Orphan of Zhao director Carey

Perloff told the cast and design team at the first rehearsal of in May. Costume

designer Linda Cho agreed, “We talked a lot about this being a story that’s

written down. It’s a legendary story.”

“The centerpiece of this whole play is when Cheng Ying finally has to tell his son who he is. But it’s so painful and frightening that he can’t—so he

paints a scroll. Cheng Bo looks at his life in the scroll and discovers who he

is,” Orphan of Zhao director Carey

Perloff told the cast and design team at the first rehearsal of in May. Costume

designer Linda Cho agreed, “We talked a lot about this being a story that’s

written down. It’s a legendary story.”

The crucial role that writing and painting play in The Orphan of Zhao led Perloff to an exhibit at New York’s

Metropolitan Museum of Art called Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China.

The exhibit, which opened in December 2013 and closed April 2014, was the first

major exhibition of Chinese contemporary art at the Met, and featured about 70

works by 35 artists.

Every piece of artwork was inspired by ink, which has been the principal medium

in Chinese art for over two millennia.>

“It’s among the most amazing contemporary work I’d ever seen,” said

Perloff of the exhibit. “It plays with this notion of inscription: What are our

stories? How do we tell our stories? What is the relationship of physical

character to those stories?” The influence of the ubiquitous nature of ink in

Chinese art is apparent in Cho’s costume design; for example, the basic unisex

costume all cast members wear is a painted tunic that looks as though it has

been dipped in ink:

“It’s among the most amazing contemporary work I’d ever seen,” said

Perloff of the exhibit. “It plays with this notion of inscription: What are our

stories? How do we tell our stories? What is the relationship of physical

character to those stories?” The influence of the ubiquitous nature of ink in

Chinese art is apparent in Cho’s costume design; for example, the basic unisex

costume all cast members wear is a painted tunic that looks as though it has

been dipped in ink: More specifically, Cho was inspired by the piece Book from the Sky,

which was first mounted in China in 1988 and has traveled the world since. The

piece, created by Xu Bing, features several large scrolls covered in what

appears to be Chinese calligraphy. However, upon closer inspection, the viewer learns

that none of the characters are actual Chinese letters, and the scrolls are gibberish.

According to curator Maxwell K. Hearn, Book

from the Sky is a response to “the often blatant contradiction between

propaganda and reality, words and actions, in a China where doctrine, news, and

history were continually being rewritten and texts could no longer be

trusted”—an analysis that also seems to fit The

Orphan of Zhao.

More specifically, Cho was inspired by the piece Book from the Sky,

which was first mounted in China in 1988 and has traveled the world since. The

piece, created by Xu Bing, features several large scrolls covered in what

appears to be Chinese calligraphy. However, upon closer inspection, the viewer learns

that none of the characters are actual Chinese letters, and the scrolls are gibberish.

According to curator Maxwell K. Hearn, Book

from the Sky is a response to “the often blatant contradiction between

propaganda and reality, words and actions, in a China where doctrine, news, and

history were continually being rewritten and texts could no longer be

trusted”—an analysis that also seems to fit The

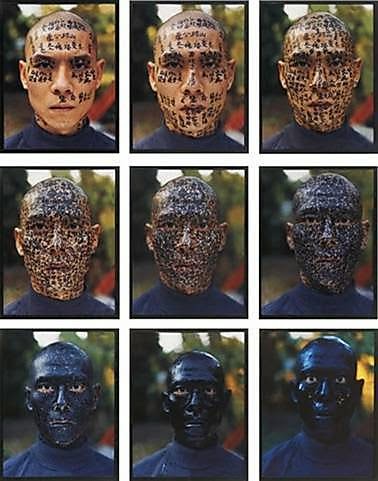

Orphan of Zhao. Cho applied a similar style of abstracted writing to the costume of the

Ballad Singer, whose beautiful poetic songs frame the show and summarize the

tale the audience is about to witness. Cho was attracted to idea of a costume

covered with unintelligible writing because it “steps away from being a historical

reproduction of anything.” This aesthetic influenced her costume design, which she

describes as “abstracted historical Chinese.”

Cho applied a similar style of abstracted writing to the costume of the

Ballad Singer, whose beautiful poetic songs frame the show and summarize the

tale the audience is about to witness. Cho was attracted to idea of a costume

covered with unintelligible writing because it “steps away from being a historical

reproduction of anything.” This aesthetic influenced her costume design, which she

describes as “abstracted historical Chinese.”

Just as Perloff and Cho found calligraphy to be central to the story of

The Orphan of Zhao, Hearn believes

that it is “China’s highest form of artistic expression as well as its most

fundamental means of communication.” Not only do the words themselves convey

meaning, but the way an artist forms

a character is significant. A practitioner might draw upon the work of artists

before him or her, and, according to Hearn, “every trace of the brush carries

the autographic handprint or ‘heartprint’ of the individual, reflective of his

or her intellect, emotions, and connection with the past. Thus have Chinese

cultural traditions been sustained and renewed.”

Read more about A.C.T.'s production of The Orphan of Zhao in

Words on Plays! Click here to purchase a copy.