Q&A with "Elektra" Translator and Adaptor Timberlake Wertenbaker

|

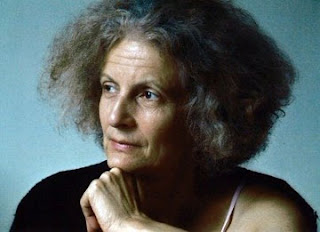

| Timberlake Wertenbaker |

Timberlake Wertenbaker—an internationally recognized, multi-award-winning playwright, translator, and adaptor—returns to A.C.T. with her beautiful new translation and adaptation of Sophocles’ Elektra, which runs October 25–November 18 at A.C.T.’s Geary Theater. She is the author of many plays for the stage and radio, notably Our Country’s Good (1988), The Love of the Nightingale (1989), and Three Birds Alighting on a Field (1992). An American-born and –educated European (she was raised in the French Basque country and studied in the United States as well as France) who has lived in London for the past three decades, she has tremendous linguistic dexterity and is a deft translator/adaptor of the great writers of European drama, including Marivaux, Anouilh, Maeterlinck, Pirandello, Euripides, and Racine. Her previous work at A.C.T. includes translations of Sophocles’ Antigone (1993), Euripides’ Hecuba (1995 and 1998), and Jean Racine’s Phèdre (2010). Below are excerpts from past interviews we’ve done with Wertenbaker over the years.

As a playwright who writes original work, what brought you to translation and adaptation, and how is the skill necessary for translation different from that needed to write an original play?

They are actually very different, which is why I like doing both. Translating is a very good way to rest from writing plays. A translation is very technical in that you are trying to put something from one language into another. It becomes more than technical, however, because you have to understand and get involved with the play. Translating requires very different parts of the brain and the emotions. I think when you’re writing a play, you’re dealing with your own imagination. You’re dealing with your own monsters, and you’re acknowledging them as your own. When you’re dealing with someone else’s characters, you’re also dealing with their heart. What makes this playwright’s heart beat? You have to try to get to know that playwright, which is why it’s very important to be able to read the text in the original language. I think it’s very difficult if you don’t. Translation is a very good way to get to know other playwrights and how they work. I enjoy it very much, and I only translate plays by playwrights that I really admire.

Where is the line between translation and adaptation, or is it a sliding scale?

I always put “translated and adapted by” [next to my name in the credits], because I translate and then I might cut five or six lines. An adaptation is something completely different. You’re freer. You just use the material. We have only three terms: “translated,” “adapted,” and “based on.” The definitions are very wide, and one term has to include something that may just be a question of cutting a couple of lines, or a very free interpretation.

Your translations have been praised for their clarity and immediacy. How did you achieve this?

I want ancient Greek translations to be modern. I think a lot of English translations have adopted a kind of nineteenth-century form to mirror the Greek, which I don’t think it does. The Greek is quite staccato and tough—it’s a very muscular language. I thought it would be good to use a very modern idiom, and to go for the argument, the logic, and the imagery of the Greek, rather than try to put it into poetic form. English verse is rather rounded—I don’t know how to explain that exactly, but I felt it would be hard for me to find an English verse form that had anything to do with the Greek. So I didn’t use verse here. It’s cut, with rhythmic, short lines—it’s rhythmical prose. I also felt that these works should be translated as plays, not as pieces of poetry.

Performances of Elektra begin October 25. Click here to learn more about the production and order tickets.